11 Feb Brain rewrites memories, Northwestern scientists say

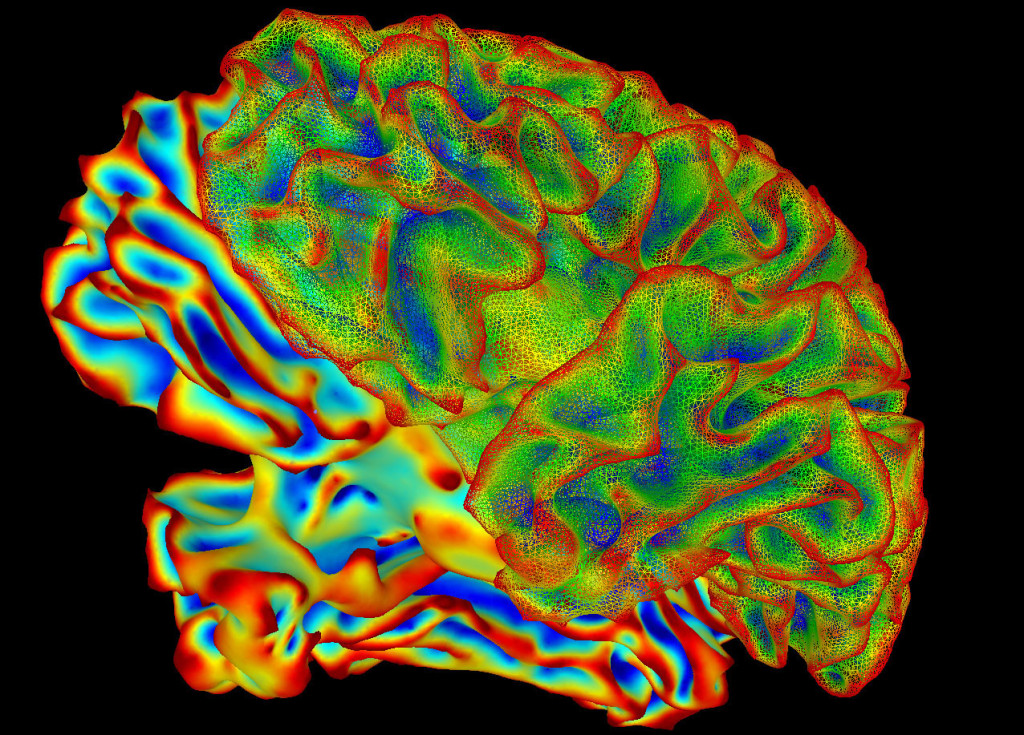

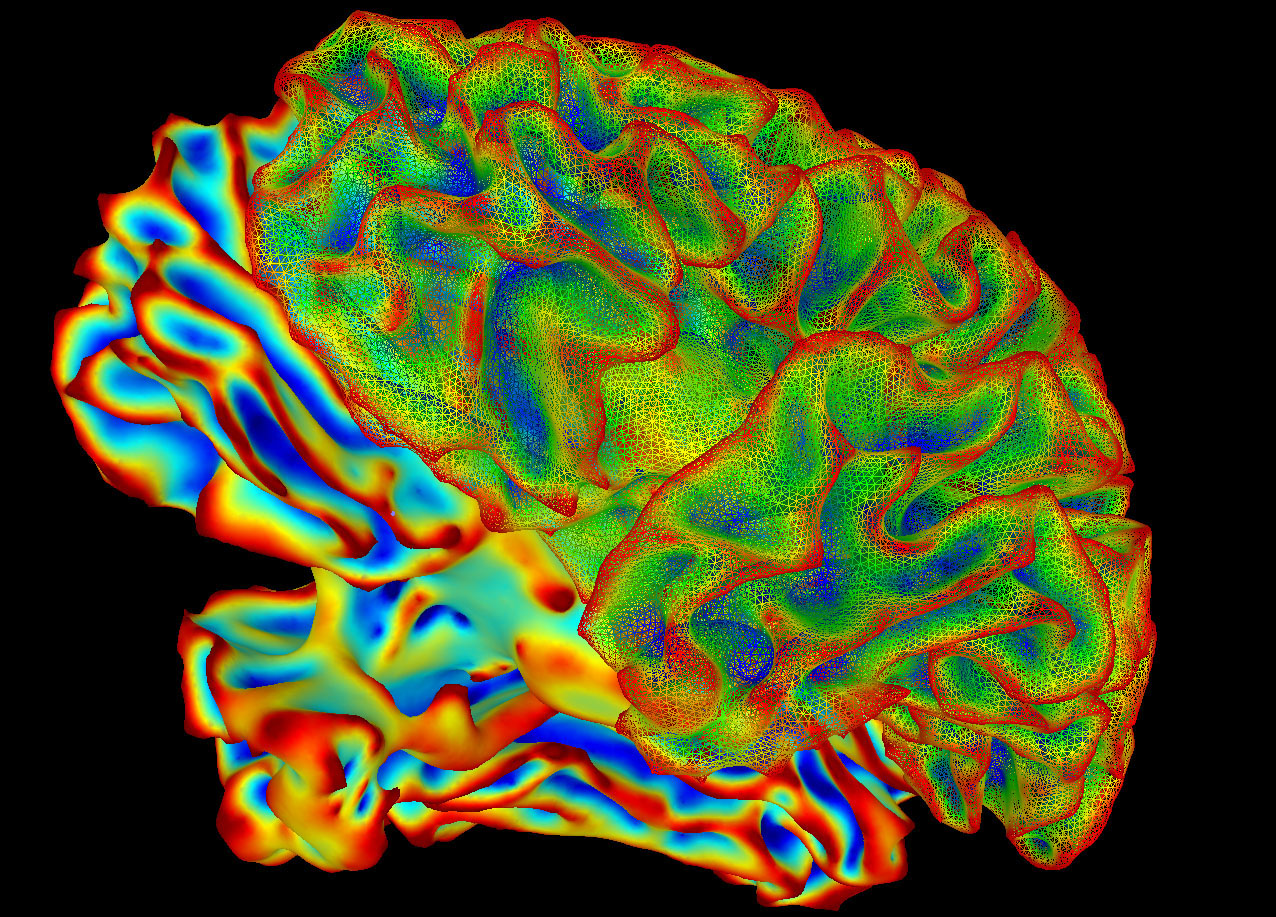

Memory02 National Institute of Mental Health picture

by Laura L. Calderone

Feb 5, 2014

Share on facebookShare on twitterShare on

reblogged from http://inside-the-brain.com/2014/02/11/does-the-brain-rewrite-memories/

The hippocampus is a portion of the brain responsible for memory and learning. Scientists from Northwestern University believe the hippocampus may update old memories when new information is learned.

Memories are not picture perfect. The brain can rewrite old memories to update them with new experiences and information, according to a new study by Northwestern University scientists published Wednesday.

“The same part of the brain that we think about for making a new memory – or making a new association – is also involved in modifying our old memories or inserting new information into our old memories to update them,” said Donna Bridge, postdoctoral fellow at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and lead author of the study.

The study, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, monitored 17 participants using three different tools: behavioral measures, a functional MRI and eye-movement tracking. Despite the number of participants appearing small, the researchers said it is a statistically robust study.

“Every person in the study showed this effect, which is rare in a psychological study,” said Joel Voss, senior author of the study and assistant professor of neurology at Feinberg. He added jokingly that he would “eat his hat” if someone who participated did not show similar results.

Participants took a test that tracked their ability to remember the locations of objects on a computer screen. They were shown an object in one part of the screen with a specific background and then told to study the object’s location. In the next phase, the participants were given a screen with an alternate background and told to place the object where they had studied it.

“During the second part when they have to move the object to where they think it belongs, they would always place it a little bit incorrectly,” Bridge said. “They never place it exactly on the pixel-by-pixel location.”

In the last part of the test, the participants were told to choose from three options: the original location, the location they moved the object in the second phase and a third new location.

“It turns out they always chose the location that they moved it in before,” Bridge said. The hippocampus was modifying the original information.

The hippocampus is a part of the brain associated with memory and learning, according Dr. Douglas Scharre, a neurologist at Ohio State University.

“We’ve known for many, many years, of course, that the hippocampus is primarily involved in the encoding of memory,” he said.

Voss said the hippocampus is also responsible for sorting through fragments of memory and “gluing” them together. When something is retrieved from the past, something in front of that person can become glued to that past memory.

“We think this modification process is actually an adaptive function of memory. We also think that it’s a basic function of memory,” Bridge said. “That our memory system is built to fail, or built to change, as opposed to stay static. It’s not just built to regurgitate facts or recreate an event fact-by-fact or piece-by-piece. Instead, it changes [memories] depending on what information is important right now.”

Damage to the hippocampus can cause problems for individuals trying to store new memories.

“We know that people have damage to the hippocampus themselves cannot store memories,” Scharre said. “They still have memories of the world and of things. So for example, you can destroy the hippocampus, but you may still know what a pencil is or a TV is.”

Bridge’s research group is trying to figure out if the adaptive function from this study can apply to those who have hippocampal impairments.

“We’re seeing if damage on one side of the brain can influence this process of modifying memories,” Bride said.

Until more research is done, it’s best to snap a picture – instead of trying to rely on the myth of picture-perfect memory.